I'm not sure exactly what I had in mind when I decided I ought to visit the village my great-grandparents' came from.My great-grandmother - we all called her "Babcia", which means grandmother in Polish - lived to be 106, so she was someone I had known personally but knew little about. I figured I was now visiting Poland for the third time, and why hadn't I bothered to do this before? I'm not into geneaology or anything, but finding this village couldn't be too difficult, since my great-uncle Tony visited there in 1988.

That must not have been a very good trip, by the way. 1988 was not a good time in Poland; I remember him telling me not to visit Poland, because it was so poor. The people in the village had offered him a pear. It was the best pear they had, but Uncle Tony described it as a terrible pear. I think it was a sad experience for him.

But, it my two previous visits to Poland, in 2000 and 2001, I had nothing but good thoughts. Sure, there were large grey Communist-looking apartment blocks, as in the rest of Eastern Europe, but the people seemed filled with optimism. They were free of Soviet shackles, and about to join the European Union, the most exclusive club of rich countries. The skies may have been gray, but the future was bright.

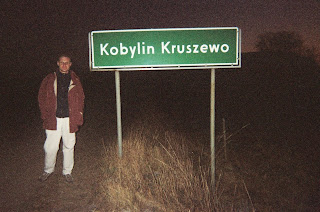

And so, my motivating philosphy in visiting Kobylin-Kruszewo – Babcia's village – was, Why not? It was there, and I would be there, and by this point I was undaunted by traveling in Poland. Of course, none of my friends lived near Kobylin-Kruszewo (pronounced “kru-SHAY-vo” – w's in Polish are pronounced as v's), which is in northeastern Poland, near Bialystok. But surely this couldn't be much of an obstacle. Somebody would help me.

So I arrived in Poland with almost no information on my antecedents. A friend of mine had made a similar visit to his great-grandparents village in Slovenia a few years ago, and he regaled me with tales of old-timers who knew his relatives buying him beers and getting him drunk. Surely this would be my experience, too!

Everything started off fine. I had gone to the website couchsurfing.com, which is a place where travelers can find people willing to host them in their homes. I searched the profiles around Bialystok, and focused on one: Sylwia, who lived in a village somewhere near Lapy, and had a car that sometimes ran. She seemed nice person, who had similar interests in the outdoors as me. I sensed she would be willing to help me. I contacted her; she was a lawyer and very busy, but she agreed to help me, as long as I came on a weekend. This was no problem, I assured her.

The time arrived in December, after I had been traveling in Europe over a month, and was circling back to Poland to head home. Sylwia lived with her parents in a house outside Lapy; her father, a mechanic, raised pigs as a hobby and killed one on the day I arrived, so we had an excellent – and very fresh! - pork dinner. Sylwia amazed me, because she was in the middle of a big, important case and had to do tons of research over the weekend, but she still made time for my little project.

On Sunday, after Sylwia spent the morning in the law library in Bialystok, we headed to Kobylin-Kruszewo. It is a very small village, of maybe 30 houses. There are no store, bar, post office, or church. And, seemingly, no people. We saw some cows, and some dogs. Sylwia knew what to do; she found the house of the town's “head man” - it had a label on the front saying as much. After a fair amount of knocking, this person showed up, and Sylwia quizzed him on the whereabouts of Sikorskis, Grodskis (Babcia's maiden name), and anybody who might be related to them. The man said that almost everybody in the town was a relative newcomer, and that there were no Sikorskis or Grodskis. Sylwia asked me if I knew the names of anyone who had stayed behind; I did not. We wandered about the village some more – it was nice, really. The homes all faced a large pastureland with a creek running through it, and there were woods behind that. We encountered two elderly villagers, and Sylwia asked them similar questions. They didn't know of any Sikorskis or Grodskis, either.

We drove to the next village, Kobylin-Borzymy, which was a bigger village. We went to the church there, where the priest showed us a shelf full of antique books listing all the births, deaths, marriages, etc., that had taken place over the past 200 or so years. I knew Babcia had been born on July 2, 1879, so we looked for that... but the elegant calligraphy in the books was not in Polish – it was in Russian! Apparently this area was controlled by Russians at that time, and everything had to be written in that language and alphabet. Which was kind of difficult for all of us: me, Sylwia, and two priests. I even had the Cyrillic alphabet cheat-sheet I made in Ukraine, which was a little bit helpful... but it would have been more helpful if the priests in those days wrote in big block letters, rather than fancy script.

But... we found her name! Teofila Grodska... or Grodskaya, as they Russianification would have it. (Okay, this photo is really blurry, but trust me on this.)

It was there in the book, and we looked for an address to maybe find out where she lived, but no luck. Sylwia wondered if I knew when she was married, or other names of relatives, but no. She also wondered how I could come to this village with so little information, but really, all my friend did in Slovenia was mention his name and the old-timers had a big party, so why should my experience be any different? Of course, my village had almost no people in it. (She also admitted that she didn't know the names of her great-grandparents, so it's not just me!)

So we went back to the village and took some more photos. Sylwia seemed a little disappointed, and said I should find out more from Uncle Tony and then she would return and find out more on her own. She was determined – perhaps more than me? It was odd. I was pretty happy to see my village and how they lived. I mean, they were farmers. It's something I figured out before, but it's interesting to see it in front of you – the land, the barns, the cows. Babcia's son Henry, my grandfather, born in the USA, was a New York City policeman, and my father is an engineer. Farming seems rather foreign to me. Yet here was the proof – Sylwia said no one could live here and not be a farmer, because that was all there was. And so, this is part of who I am. That to me was a success.

After returning home I called Uncle Tony and found out some more information. While he didn't have any addresses and didn't know the names of any relatives who stayed behind, he did tell me that Marcelli Sikorski, my great-grandfather, came from a different village, Sikory-Pawlowieta, farther down the road. The two didn't meet there, they met in America, and were married at a church in Brooklyn. Babcia had left from Bremen, Germany, on a ship called the Weimar in 1901. Uncle Tony had had copies of both birth certificates translated from the Russian, and confirmed that the parents had been part-owners of farms.

I passed this information along to Sylwia, who remains determined to figure out my past. It looks like I'll have to go back to Poland again. Sooner or later, there will be a party for me, I'm sure of it.